North America’s newest rapid transit service, the Réseau express métropolitain (REM), opened on Monday, July 31, 2023 after a weekend of free public rides. I took my first ride several weeks later, on August 22, 2023. The five stop, 16.6-kilometre line between Central Station and Autoroute 30 in Brossard, is the first of four phases of the initial REM network, with branches north and west of Downtown Montreal to open in the next few years.

Built by the CDPQ Infra, a division of Caisse de dépôt et placement du Québec (a provincial public pension fund), REM is a light metro network connecting suburban communities with Montreal’s urban core. With limited stops, a downtown-suburban focus, and frequent service, REM has similarities to Bay Area Rapid Transit (BART) in the San Francisco metro region, to S-Bahn systems in Germany and Austria, or RER in metropolitan Paris. Like Vancouver’s SkyTrain or the future Ontario Line here in Toronto, the trains are short, and operate fully automatically, running every 3.5 minutes during weekday peak periods, and every 7.5 minutes at all other times, from 5:30 AM until after midnight.

As REM is being built by a pension fund — which seeks to make an 8% return on building and operating the service — financing the line is a bit different. Though it received financing from the Canada Infrastructure Bank and support from the provincial government, much of the funding comes from other sources, such as development levees. It is also guaranteed a share of fare revenue from the provincial government.

Though several notable transport enthusiasts have already documented the new REM during its opening weekend, I wanted to wait for some of the excitement to wane; I also wanted to experience the service from a regular passenger’s point of view, including checking out the stations and transfers to other transit operators.

For the most part, I came away satisfied. However, I encountered several shortcomings, particularly with service integration and transfers between modes.

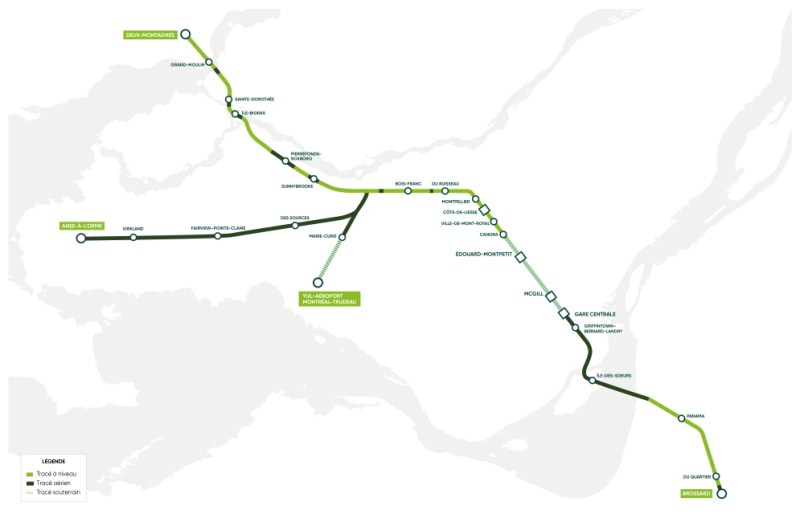

The network

The Montreal-Brossard segment is the first part of a four-branch network serving Montreal’s South Shore, West Island, and North Shore. The first phase that opened last month begins at Central Station, makes a stop at Île des Sœurs (Nuns’ Island) before crossing the St. Lawrence River on the new Champlain Bridge. It then follows Autoroute 10 south through the suburban municipality of Brossard, before terminating south of the Autoroute 10/30 interchange. The trip is quite speedy. Riding from Brossard to Central Station takes 19 minutes, with the fastest cruising speeds (80 km/h) made on the Champlain Bridge.

The next phases will take REM trains through the renovated 110-year-old Mont-Royal Tunnel (including new tunneled stations at McGill Metro and at Édouard-Montpetit Metro, near Université de Montréal) and over the former electrified Deux-Montagnes commuter rail line, with branches to Deux-Montagnes, the West Island, and Trudeau (Dorval) Airport.

Though the REM south section opened nearly two years later than initially projected (and the central section through the Mount Royal Tunnel, along with the Deux-Montanges and West Island branches now expected to open in late 2024), construction only began in April 2018. When compared to delayed or failed rail transit project launches in cities like Edmonton, Ottawa, or Toronto, though, REM has so far been a relative success, despite a few glitches in the first week of revenue service.

Part of the reason REM has been relatively quick to build was that the route follows existing rights-of-way, including the new Champlain Bridge, which had a purpose-built transit deck included as part of that massive project, as well as highway medians and existing rail lines.

Though CDPQ is a public pension fund, and operates independently from the provincial government, it still benefitted from cooperation from the Ministry of Transport for the use of the Autoroute 10 median, and the transfer of Exo’s Mont Royal Tunnel and Deux-Montagnes line to REM. Without new tunnels to dig (except for the airport branch) or lands to expropriate, much of the early works could be avoided. Otherwise, the route utilizes elevated guideways or at-grade alignments.

Interestingly, the central portion — the Deux-Montanges Line — would have been Metro Line 3 in the original plans for the Montreal’s rapid transit network. Unlike other Metro lines it would have used conventional steel-on-steel traction and would have operated on the surface north of Mont Royal. However, Expo ’67 accelerated the need for Line 4 — the Yellow Line to Île Sainte-Hélène (the Expo site) and Longueuil, while the 1976 Summer Olympics accelerated expansion plans eastward.

With the construction of REM — including the interchange with Metro Line 5 (Blue Line) at Édouard-Montpetit — the 60-year-old plans for Line 3 will finally be fulfilled.

In 1992, the old CN-operated electric service was shut down for major reconstruction, with modern EMUs operated by the Agence Métropolitaine de transport (AMT, the predecessor to Exo/ARTM) taking over in 1995. The electric passenger service — Canada’s only mainline electric passenger railway — shut down in 2020 for REM construction.

One thing that I also appreciated were the full-height platform edge doors at every station. Though UP Express has platform doors at Union Station and at Pearson Airport, REM is only the second public transit system in North America to feature platform edge doors at all stops, Honolulu’s Skyline, which opened in June, was the first.

Platform doors are not only a security measure — especially beneficial for a fully automated system with limited staffing — they also help keep the stations at a comfortable temperature.

Regional fare reform

Ahead of REM’s opening, the Autorité régionale de transport métropolitain (ARTM), a provincial transit agency similar to the GTHA’s Metrolinx, developed a new simplified fare zone scheme that corresponds to the local transit operating regions in Greater Montreal.

Though not advanced by the CDPQ nor was it necessary for the REM’s operations (it could have used a separate fare structure), the new fare structure is certainly beneficial to REM riders, particularly those transferring from other transit services.

Prior to the new ARTM fares, introduced in 2021, each transit agency — Société de transport de Montréal (STM), Société de transport de Laval (STL), Réseau de transport de Longueuil (RTL), in addition to Exo buses serving outer suburbs — had their own fare pricing schemes, with limited fare integration with Exo commuter trains. The new fare structure covers all modes, facilitating easier transfers.

For example, a Zone AB fare would allow one to take the Metro to Bonaventure Station, transfer to REM at Central Station (more on that below), then transfer to an RTL bus on a single adult $4.50 fare. A 24-hour pass costs $12.75, which allows unlimited travel on STM, STL. RTL, REM and Exo trains within Zones A and B.

The 24-hour daypass is a bargain compared to Toronto. A day pass (only good for a calendar day, not a continuous 24 hours) costs $13.50, does not include passage on GO buses and trains, and cannot be used for any neighbouring transit services. For travel just within Montreal, the 24-hour pass costs $11.00.

The first phase of REM and the new regional fare structure has allowed RTL and Exo to divert hundreds of buses daily from the Champlain Bridge and Downtown Montreal to the Brossard and Panama terminals. Though many South Shore passengers lost a one-seat ride, they now have a more reliable commute.

Stations, transfers, and transit-oriented development

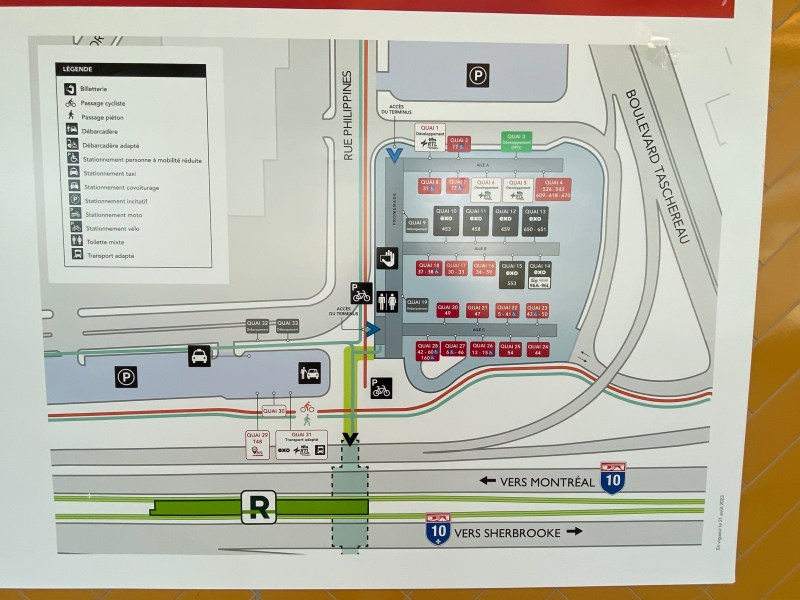

Brossard terminal, at the south end of the line, abuts the Autoroute 10/30 interchange, and like many suburban GO Transit stations, the station property’s most prominent feature is a massive parking lot, with space for 2,950 vehicles, including reserved paid spots and carpool lots, both close to the station’s front entrance. Next to the parking area is the main REM maintenance and storage facility. On the other side of the station is a large bus terminal, mostly serving Exo local and commuter routes to suburbs like La Prairie and Saint-Constant, and outlying towns such as Chambly and Mont-Saint-Hilaire. New highway ramps provide easy access to the bus terminal and parking lot. Given the limited development opportunity of the immediate area (constrained by highways and hydro corridors), I have few complaints about the location or layout of this terminal station.

The only major drawback that I found at Brossard Station — which I also encountered at Panama Station — is the bus terminal layout and access for suburban and regional buses. The bus terminal, shaped like a giant “U”, is a completely separate building from the REM station. The sprawling station features long walks from many bus platforms to the main terminal area, where a door leads outside, towards the REM station. Though the walkways are sheltered, transfers here will not be pleasant. Though the fares may be integrated, the bus transfers are not quite there.

The three intermediate stations — Du Quartier, Panama, and Île-des-Sœurs — are all located in the median of Autoroute 10. The stations themselves are very simple box-shaped structures with a platform level and a fare concourse at street level.

Du Quartier Station is just to the north of Autoroute 30, in a newly urbanizing section of Brossard. On the west side is a 1990s-era big-box plaza, which is connected to the REM by a long enclosed walkway. Just north of the big box plaza is a newer phase of the Quartier DIX30 retail development in the outdoor “lifestyle centre” model similar to Shops at Don Mills, with underground parking and walkable “streets.” Like Shops at Don Mills, Quartier DIX30 has many restaurants and high-end retail tenants centred around a large plaza.

Despite the car-centric nature of Quartier DIX30, particularly the older southern half, there are opportunities for new urban development. On the east side of the REM station, this is already happening.

A new, midride, mixed-use neighbourhood is already well-advanced in development. Already, there are several apartment buildings, offices, shops, restaurants, public spaces and a hotel, all within a short walk of the REM station. (The new Courtyard Marriott, where I stayed, is very convenient to the station.)

This development also helps to finance the REM through construction levies for work completed within a one-kilometre radius of REM stations.

The area Île-des-Sœurs Station is also slated for new development, with residential development planned or under way on both sides of the station.

At Panama Station (named for a nearby street), the main transfer point between RTL buses and the REM (along with several local Exo buses to Saint-Constant and Delson), the disconnect between the separate transit facilities is apparent. The Panama Terminal is gigantic, with dozens of connecting buses.

There is only one passage between REM trains and buses: via an outdoor breezeway, which, unlike Brossard, is covered to protect from the summer sun and from rain.

However, the most awkward connection is between Metro trains and REM trains at Montreal Central Station, though for most passengers, it is at least fully enclosed.

It took me six minutes to get from getting off a train at Bonaventure Metro Station to the fare-paid area of the REM at Central Station. This is not a new problem; I am awfully familiar with the convoluted connection (which involves three sets of escalators, two short staircases, one longer staircase, and four sets of doors to open and pass through) as I am a regular VIA Rail passenger. Though it took me six minutes to complete the walk, for someone unfamiliar with the route between trains, or anyone with luggage, children, or with mobility challenges, it is even more difficult, especially for anyone requiring elevator access. Though Bonaventure Metro now has elevators, it requires an outdoor transfer to get to the train station. While I vested in August, the main elevator from the street level at Central Station to the REM concourse was out of service.

The video I took below, at 3x speed, shows how complicated the transfer is. I added an appropriate soundtrack.

Music: “Cant Get There from Here” by R.E.M., from Fables of the Reconstruction, released 1985.

Hopefully, the connection at McGill Station to the Green Line will be smoother when it opens at the end of next year.

For the most part, I enjoyed my rides on REM. It is rare to have the opportunity to ride a brand-new transit project in Canada, especially one that is as innovative as this. One of the unique joys was seeing all the children (and children-at-heart) crowding the front of each train as it passed. Transit should always be a little bit joyful.

There are some criticisms, disappointments, and concerns for the future.

As REM was built with the expectation of an 8% return on investment by a pension fund, what happens if it does not reach that goal? Who will be left on the hook?

Why was REM able to keep its stations separate from the connecting buses? Why was wayfinding so poor that a Concordia University student felt that he had to intervene on his own accord? And why isn’t the tunnel to Trudeau Airport extended just 700 metres to make one more stop to the Dorval VIA and Exo stations, for better connectivity? And why was REM allowed to monopolize the Mont Royal Tunnel?

All that said, I do look forward to returning in 2024-2025 to ride the new extensions. Montreal is one of my favourite cities, and it doesn’t take much of an excuse to ride the train for another visit.