I recently visited two Ontario cities, St. Catharines and Orillia, to illustrate the problems of building new medical and educational institutions on isolated greenfield sites.

Large greenfield lands have several advantages: they’re easy and inexpensive to build on, they can accommodate large parking lots, and offer room for future expansion. But by the nature of their isolation, they’re more expensive to serve with road and water infrastructure, and more difficult to connect to transit. Students, patients, and employees must travel farther, and they don’t foster economic and social connections with the local community as well.

St. Catharines

In 2013, a new hospital campus opened in St. Catharines, replacing two smaller, run-down hospital sites just outside of the city’s downtown core. The new Niagara Health System site offers new and improved services, such as regional cancer centre, a spacious and bright dialysis unit, and a modern mental health centre. When the site opened, it was a vast improvement over the older facilities.

But there was one, major, drawback: the new hospital site is located on the far western edge of St. Catharines’ suburban sprawl, almost inaccessible without a car.

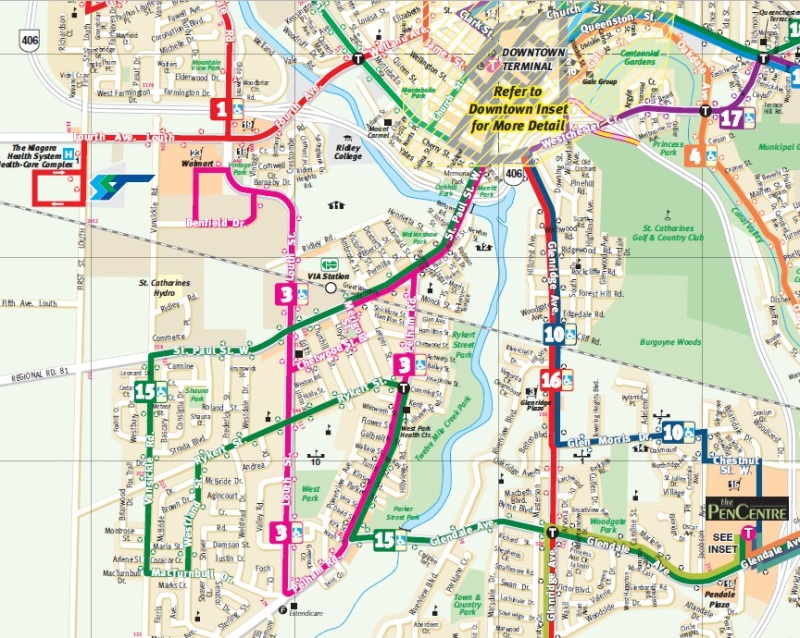

Location of current and former St. Catharines hospital sites

St. Catharines Transit re-routed a bus route (Route 1) to serve the new hospital site, but it costs the transit system nearly $400,000 a year to do so. The old General Hospital had four bus routes within walking distance to its urban location. Passengers from Thorold, Merritton, or several other neighbourhoods are required to make an additional transfer at the downtown bus terminal in order to access the new site. The distance makes taxi trips more expensive for the majority of St. Catharines residents and more difficult to get to by foot or by bike.

The old St. Catharines General Hospital on Queenston Road just east of Downtown, is fenced off, awaiting demolition. The old hospital site is a century old and constrained, and it’s easy to see why a new modern hospital was preferred over renovation and expansion of the existing facilities. The surrounding neighbourhood is economically deprived. Previously, the hospital and its associated medical offices provided local employment, and hospital workers and visitors would patronize local businesses. With the hospital gone, the neighbourhood has visibly declined.

North of the old St. Catharines General Hospital, closer to the Queen Elizabeth Way, there are numerous large brownfields that could have been remediated and used for the new hospital. An old General Motors forge and transmission plant, located just north of the Hotel Dieu hospital site, closed in 2010 and is now being demolished, could have been another useful site. Locating the hospital in one of these locations would have kept jobs and medical services closer to the downtown core, and to economically deprived neighbourhoods.

Happily, Downtown St. Catharines is seeing some new public and commercial investment. The OHL Niagara IceDogs play in a new downtown arena, connected to St. Paul Street, the main commercial artery. Nearby, a new performing arts centre was built, on the site of an old motel. Brock University converted an old textile mill into its new school of fine arts. The large student population — as well as municipal and provincial office workers — frequent the cafes, restaurants, bars, salons, and boutiques, making for a relatively vibrant business district.

The Canada Hair Cloth Company factory in Downtown St. Catharines is now the Brock University Marilyn I. Walker School of Fine and Performing Arts.

Orillia

Orillia, a 90 minutes’ drive north of Toronto, is a small, picturesque city of 31,000 people. In 2010, Lakehead University, based in Thunder Bay, opened a satellite campus in Orillia. Even though the city had plenty of disused industrial and railway lands just south of its downtown core, Lakehead opted for a greenfield site on the other side of the Highway 11 bypass.

Without a car, Lakehead students are isolated, far from any shops, restaurants, bars, or even connections to other cities. Students must take a bus to get downtown (which has restaurants, art galleries, even a bookstore), and transfer to get to the Ontario Northland bus station, located in a former railway station to the south. The closest retail to Lakehead’s campus is a Costco big-box store, an 8 minute walk away.

Lakehead University Orillia campus entrance

In the 1960s and 1970s, as Ontario’s network of colleges and universities expanded, new greenfield campuses in suburban and exurban locales came into vogue. York University is the largest and most notable example, but others include Brock University in St. Catharines, University of Waterloo, Durham College in Oshawa, and Algonquin College in Nepean. Many of these campuses saw the city grow around them. York University, Algonquin College and the University of Waterloo will soon be linked to their nearest urban centres by new rapid transit lines. But Brock, Trent University in Peterborough, and many community college campus — Loyalist College in Belleville in particular — remain isolated, dependent on cars or long transit trips, to access.

You might think that we’ve learned from these mistakes, but we haven’t. The City of Orillia had plenty of other sites that would have been more suited to a small university campus.

Orillia’s Georgian College campus is located on Memorial Avenue, on Orillia’s south outskirts. Nearby is the Ontario Provincial Police headquarters and the Huronia Regional Centre, a shuttered provincial residential institution for children and adults with disabilities. The Huronia Centre is still partially used for provincial offices and the OPP Academy. Had Lakehead located here, it would at least be adjacent to other educational uses; Orillia Transit already operated a bus to serve this area. Humber College’s Lakeshore Campus masterfully re-purposed a former mental health facility; Lakehead could have done the same.

Just south of Downtown Orillia, there’s a large, mostly empty industrial area that was vacated in the 1980s and 1990s (here’s what it looked like in the 1960s). Canadian National pulled out its tracks in 1996, and passenger rail service came to an end. However, the old railway station remains in use for Ontario Northland buses to North Bay, Barrie, and Toronto.

Had Lakehead’s campus been located here, it would have provided a needed boost to this derelict part of what is otherwise a pretty little city. Downtown, and the intercity buses, would be a mere 10 minute walk away. Many students work part-time jobs to help fund their tuition fees and the cost of living away from home; locating post-secondary educations close to those types of jobs would be beneficial. Students benefit from a variety of nearby off-campus places to eat, drink and have fun.

Many universities have realized that they are an essential part of the community they are located in. Ryerson University, for example, integrated with Downtown Toronto it’s surrounded by, has embraced its role in city building. Isolated campuses don’t lend themselves as easily to these sort of symbiotic relationships.

Derelict industrial area south of Downtown Orillia

As I discussed here before, the Town of Milton wants to make the same mistake with its Education Village, locating it as far as possible from its quaint downtown core, and even farther from the GO Station.Brampton, which also got a provincial go-ahead for perusing a new university campus, could either follow Milton and Orillia’s examples, or locate close to downtown and transit.

A new megahospital site is planned for Windsor, but in a farmfield that is even more isolated from the city than St. Catharines’ new hospital. Windsor Transit estimated that it could cost $2 million a year to service that site. New water and wastewater pipes have to be built to service it. At the same time, the closed GM Transmission Plant on Walker Road is being demolished; it would have all the necessary utilities and services nearby.

Greenfield sites can be very attractive. They’re spacious, often less expensive to purchase, and are ready-to-build. There’s no demolition necessary, no cleanup of industrial contamination, no neighbours to consult. They’re popular with suburban politicians.

It’s not difficult to understand why important uses such as hospitals and university campuses are built. But they come at other costs. Hospitals need to be accessible to the population they serve. University and college students benefit from urban campuses, and so do local merchants. Local transit systems naturally serve urban areas; it costs them more to gerrymander routes out to greenfield campuses.

As public sector employers like hospitals, universities and local governments are now the main employers in many cities and towns across North America, doesn’t it make sense to locate them where it’s easy for their employees to get to, especially without a car? Parking lots, as I’ve argued before, are expensive to build and maintain.

And while the province claims to be in favour of “Smart Growth,” they’re the main funding agency for university and hospitals. Instead of leading the way by encouraging infill development that promotes transit use and active transportation, the province is okay with this. That’s a shame.

2 replies on “Greenfield infrastructure: not so green”

The most convenient method of transportation to these suburban campuses is probably a car. 1) For educational institutions, the only students who could probably afford a car are those living with their parents. 2) For some medical medical procedures you aren’t supposed to drive afterward. 3) Despite their locations, they often insist on charging “downtown” rates for parking.

Thanks for bringing attention to this issue – I’m always impressed that you’re willing to make it out to Niagara for these types of analyses!

We have a lot of work to do here: among nearly all of my high school friends and family members here in Niagara Falls, very few can even understand why we think about this. Maybe the rising house prices will cause market forces to induce some intensification; I’m more worried that they will instead lead to a provincial government that declares a full-on assault on the Greenbelt “out of necessity.”