Less than a two hours drive or train ride from Toronto, where that city’s first light rail line opened to universal disdain, a light rail line has been operating without incident for over five years. Trains operate like clockwork, signal priority works, and it has become the backbone of a regional transit system.

Though the Ion LRT project was subject to several delays, opening eighteen months behind schedule, operations have been notably smooth since the public opening on June 21, 2019. The delay is attributed to Bombardier’s late delivery of their Flexity light rail vehicles, which were built on the same assembly line as the TTC’s new streetcars.

Funded by all three levels of government, the Ion LRT was constructed and operated by GrandLinq, a public-private partnership (P3) consortium that includes operator Keolis and engineering and construction firms such as Aecon, Kiewit, and Plenary Group. Though design-build-operate P3 models are common for Canadian transit infrastructure projects, they have their challenges, as Waterloo Region would later find out. Fares and service are integrated into the Grand River Transit bus system, which is owned and operated by the regional government.

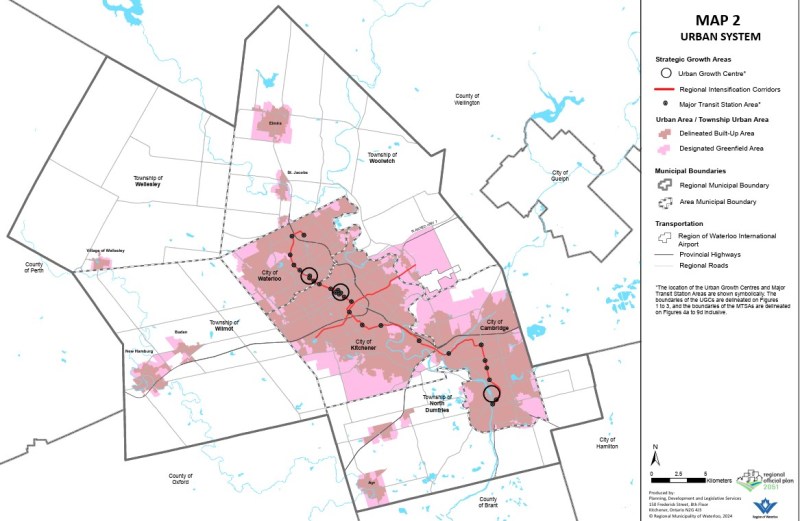

Waterloo Region is the smallest urban region in North America with a light rail system, and it works largely because of Kitchener-Waterloo’s geography. Many important regional destinations line up along the corridor: the terminals are both major suburban shopping centres that already functioned as major bus transfer points. In between the two malls are Downtown Kitchener and Uptown Waterloo, the two historic town centres, University of Waterloo, Wilfrid Laurier University, and Kitchener-Waterloo Hospital. The LRT serves or passes near all these destinations (though Laurier’s campus is centred a few blocks east of the LRT corridor). Furthermore, the region’s master plan focuses urban growth along the LRT corridor with new high-rise residential and mixed-use development. A planned extension of the LRT into Cambridge south to the historic Galt town centre will further support regional urban intensification goals.

Ion trains operate every 10 minutes during weekday daytime hours; they operate every 15 minutes on weekends and weekday evenings, with 30-minute service from about 10:30 PM to the end of service starting around midnight.

Despite following a linear corridor, the LRT winds its way along city streets, railway rights-of-way, and hydro corridors. This allowed the region to reduce property and road construction costs as well as achieve higher speeds in specific off-road sections. The fastest section is north of Uptown Waterloo, where the corridor makes use of a freight railway spur line between Kitchener and Elmira that also happens to run directly past University of Waterloo. In the south end, a different railway corridor and a hydro corridor allow trains to reach Fairview Park Mall on a mostly off-street alignment. These off-road segments are protected by railway signals and barriers, like those in along LRT lines in Calgary and Edmonton.

This ability to switch between different alignment types is a clear advantage of light rail transit for medium-capacity transit systems. During overnight hours, freight trains headed to a plastics plant in Elmira use the same rails north of Uptown Waterloo as the LRT does during the day, making it an example of the “tram-train” model more common in Europe.

The on-street sections, though slower than the off-road portions, provide access to Downtown Kitchener and Uptown Waterloo, including the planned new transit hub in Downtown Kitchener that will provide a better connection to GO Transit trains to Toronto. Unlike Toronto’s streetcars and Finch West LRT, however, the signal priority system works. On King Street between Downtown and Uptown, there are many intersections with traffic signals, but the LRTs generally do not have to stop at any of those red lights. At intersections, LRVs continue at regular speed, typically 40 km/h through this section.

Waterloo Region also worked to permit unique transit signals, which feature only white bar aspects. A vertical bar indicates “proceed” while a horizonal bar indicates “stop.” A flashing horizontal bar lets the operator know that it will soon switch to “proceed” while a flashing vertical bar warns of an upcoming stop signal. This reduces the sign clutter that is found on Toronto’s streetcar and light rail corridors.

To be fair, the advantage in Waterloo Region is that most of the on-street sections of the LRV corridor are on narrower urban streets rather than suburban arterials like Finch Avenue. King Street and Charles Street in Kitchener only have two general traffic lanes and are not major throughfares (a provincially-maintained freeway between St. Jacobs, Waterloo, Kitchener, and Highway 401 absorbs much of this traffic). The regional government also widened a section of Weber Street to four lanes to divert traffic from King ahead of LRT construction. This resulted in the loss of about two dozen houses and businesses.

But by maintaining a narrow right-of-way on King Street, the LRT runs with minimal delays. It is easier to provide aggressive transit signal priority with short pedestrian crossing distances, narrow intersections, and lower traffic volumes.

The video below illustrates how the LRT runs along King Street northbound from Kitchener Central Station.

Despite the LRT working well, it is still far from perfect: there are several sections in which the trams crawl at a 10 or 15 km/h speed, particularly on the south end. At Hayward Avenue the route switches from a railway corridor to an alignment alongside Courtland Avenue; this section has two tight turns and crosses an industrial driveway. Had a few more properties been expropriated (at additional cost) this would not have been an issue. Until a proper protected pedestrian crossing is installed at a path connecting Trayner Avenue to Fairway Road (a critical pedestrian link that was overlooked during the planning phase), LRVs must also slow down along the hydro corridor approaching Fairview Park Mall.

The P3 contract also limits the ability to make service improvements. In 2024, Waterloo Region proposed revising the LRT schedule to run trains every eight minutes during peak periods, but because of a fixed staffing contract, it would have resulted in 30-minute service after 8PM. Luckily, local transit advocates successfully opposed that change. Had the LRT been operated directly by Grand River Transit, they could have simply trained more operators on the LRT service, even transferring bus drivers to the rail division.

Overall, however, the LRT works in Waterloo Region both as a transit service and a planning tool. It provides useful lessons on what to do (real signal priority and proper signal aspects, make effective use of on-street and off-street routing where each makes sense), and what not to do (enter strict operating contracts) when building a new transit line. Waterloo Region made its rail transit work for its geography and its needs, and that is the most important thing.