With planning now well underway for the Alto high speed passenger rail corridor between Quebec City and Toronto, there has been some speculation that Ottawa’s grand old Union Station, in the heart of the capital’s downtown core and a mere stone’s throw from Parliament Hill, could see trains again. Local business leaders and Mayor Mark Sutcliffe are excited by the idea of a downtown station, expecting that a downtown transport hub would help revitalize the local economy. Though it’s a very attractive idea, there are unfortunately just too many reasons why this would not be feasible.

To understand why, it’s worth diving into the history and urban politics of railways in the National Capital Region.

The decline and closure of Ottawa Union Station

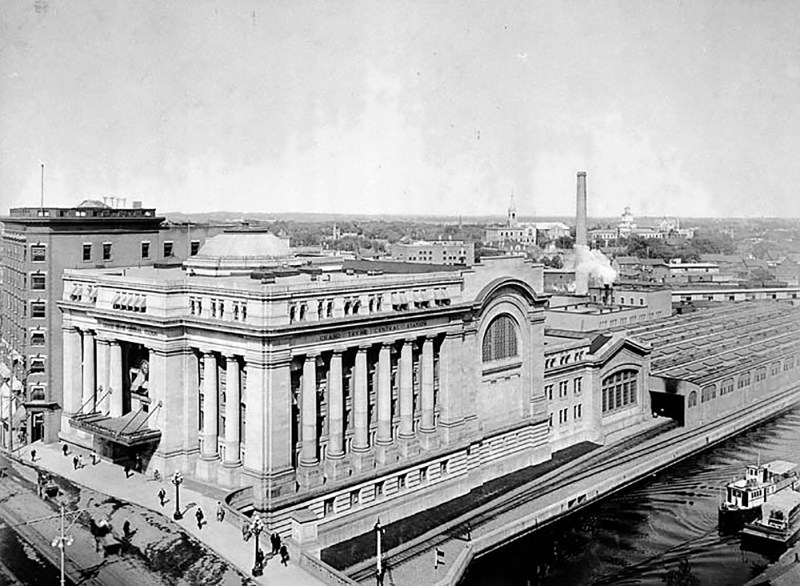

The Grand Trunk Central Station, opened in 1912, provided a grand entrance to Canada’s capital city that was previously served by a few smaller stations just outside the downtown core. The station, designed in the Beaux-Arts style, was built as a stub-end terminal. This meant that trains would arrive and depart from the south and would have to be backed up to change direction. This suited the Grand Trunk Railway just fine, as it lined up perfectly with its route to Montréal via Alexandria (still used by VIA Rail today). The railway also built a hotel across the street — the Chateau Laurier — and connected the station with the hotel with a pedestrian tunnel.

The 1912 station was intermodal from the very beginning. Right outside the station’s front doors, there were Ottawa Electric Railway streetcar platforms serving several routes on Rideau and Sparks Streets, the two main commercial corridors in Downtown Ottawa. Right below the canal and railway bridge next to the station was the Hull Electric Railway’s loop; its streetcars crossed into Ontario via the Alexandra Bridge.

Soon after opening, the Canadian Pacific Railway joined the Grand Trunk, resulting in the terminal being renamed Union Station; the short-lived Canadian Northern Railway (CNoR) soon followed. As the CPR’s tracks to Hull (via the Alexandra Bridge) ran next to the GTR’s station, it suited the CPR well. Unlike Grand Trunk, both the CPR and CNoR had direct lines to Toronto.

Two platforms on the west side of the station allowed through CPR trains to continue towards the Alexandra Bridge and even return to Ottawa via the Prince of Wales Bridge to the west; this was the route the iconic Canadian train between Montréal and Vancouver took when it was inaugurated in 1955. Most trains — including all GTR and CNoR, however, terminated at the six stub-end tracks. Both GTR and CNoR were absorbed into the new Canadian National Railway (CN) by 1922.

In the 1940s, the federal government led by Liberal prime minister William Lyon Mackenzie King wanted to beautify the nation’s capital region and address traffic congestion. Ottawa — and the federal government — was rapidly growing, while political leaders wanted a cityscape that matched the ambitions of an expanding nation. French urban planner Jacques Gréber was commissioned to plan the region’s future; Gréber’s recommendations, released in 1950, were ambitious and transformative. (You can read the entire report here.)

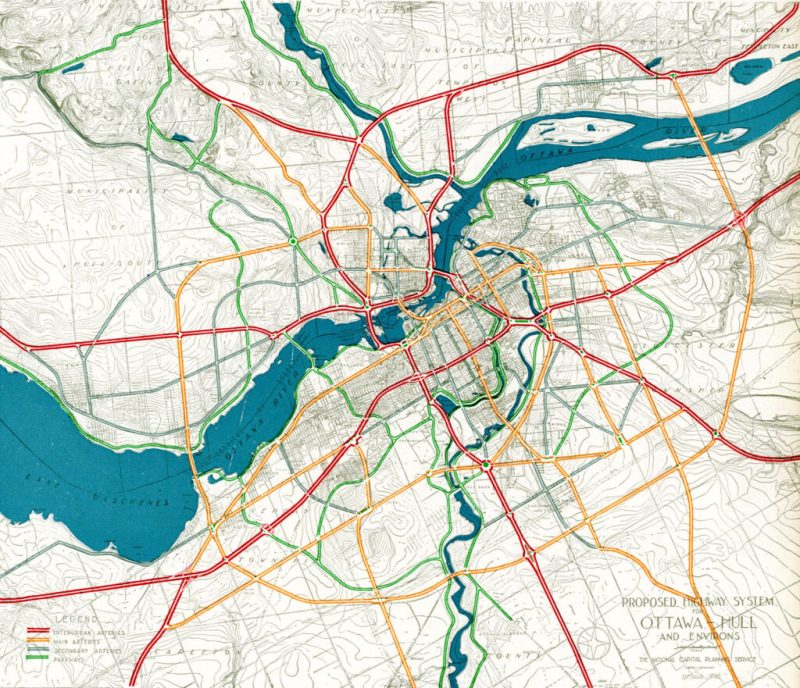

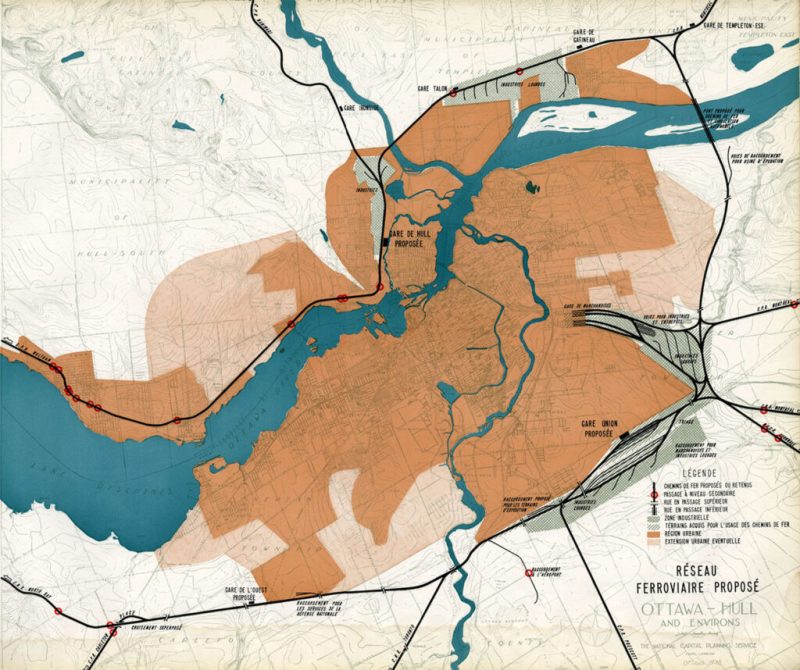

The Gréber Plan — formally titled “Plan for the National Capital” — called for new highways, the abandonment of Ottawa’s streetcars (which were seen as antiquated with unsightly overhead wires), and the removal of all railway infrastructure within the City of Ottawa. The old CN and CPR lines would make way for new roads, including a four-lane arterial along the east side of the Rideau Canal, leading to a new road bridge replacing the Alexandra. A new railway bypass along the periphery of the city would replace all urban trackage, with a proposed new Union Station site in Gloucester Township, south of Walkley Road. Most industrial uses — including the historic paper mills along the Ottawa River — would be moved to the new railway line.

Though the plan was not fully implemented, it did set the stage for much of the urban planning and infrastructure changes during Ottawa’s next fifty years. The railway bypass was constructed between Bell’s Corners in the west and Ramsayville in the east, with the old Grand Trunk tracks through the city replaced with The Queensway, now part of Highway 417. New parkways lined the rivers and canals. Two new multilane traffic bridges crossed the Ottawa River (though the Alexandra Bridge was maintained for traffic and pedestrians) and Albert and Slater Streets were made one-way, with a new bridge over the Rideau Canal (the Mackenzie King Bridge) linking them to the east. A large Greenbelt encompassed the city region, intended to direct growth while preserving natural areas.

Fortunately, the passenger station was relocated to a point much closer to the city centre than the Gréber Plan envisioned: the old CN and CP tracks along the Rideau River south of the city centre were kept in place but rerouted to serve a new modernist station that opened in July 1966. The new Ottawa Station, designed by John C. Parkin, is one-of-kind. The architecture invokes an airport terminal, with large, sheltered driveways and an airy open lobby/concourse, and was the last grand railway station built in North America. In 1966-1967, there were still two daily transcontinental trains departing from Ottawa Station, along with multiple trains to Toronto and Montreal, including a Toronto-Ottawa night train. Today, there are just eight trains to Toronto and five trains to Montréal.

Soon after the new station opened, the tracks and ancillary buildings around Union Station were removed, making way for Colonel By Drive, the Rideau Centre shopping mall, a new convention centre, and headquarters for the Department of Defense. The station building itself survived, however, first becoming a temporary museum space during the 1967 Centennial celebrations, then a government conference centre, mostly closed off to the public.

Right now, the grand building is the temporary home of Canada’s Senate, and is again accessible to the public, via a free tour. The renovations to the building are very sympathetic to the built heritage. As reconstruction of Centre Block, the regular home of both Houses of Parliament, is still five years away from completion, there’s still lots of time to take the tour.

Awaiting Alto

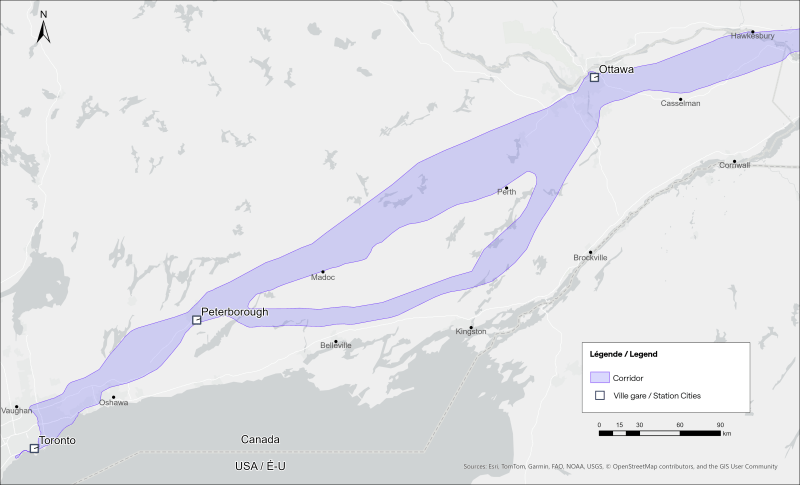

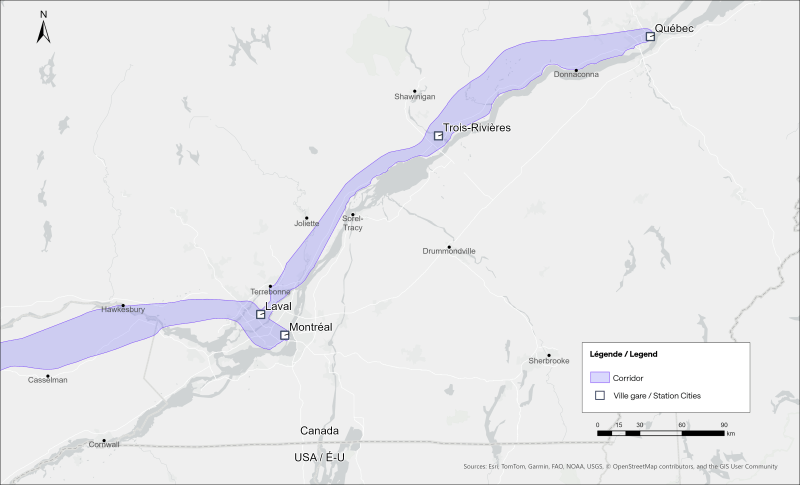

The Alto high speed rail line project, now in the planning stage, will connect Québec, Montréal, Ottawa, and Toronto, with a total of seven stations (the other three are planned in Trois-Rivières, Laval, and Peterborough). The first segment, with the start of construction set for 2029, will link Montréal, Laval, and Ottawa. Consultations on the specific route and station locations are underway, with the broad corridors noted in maps available on the Alto website.

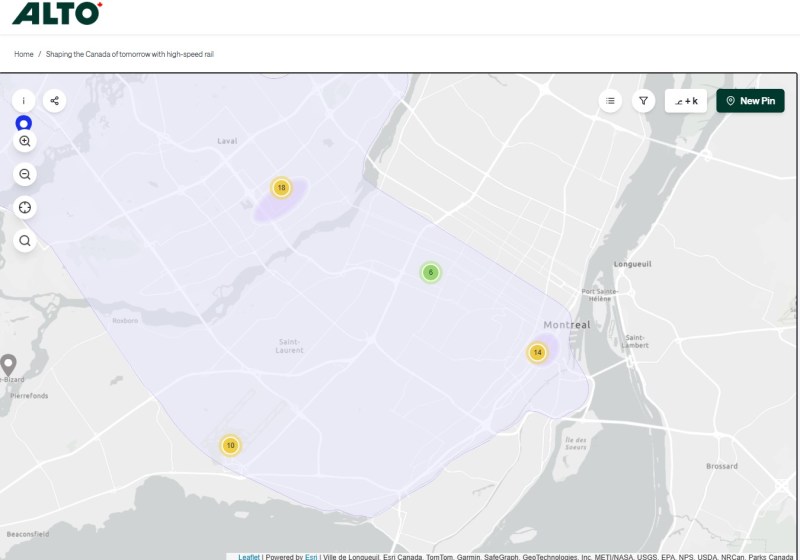

The maps clearly show a route between Ottawa and Montréal that will pass through Prescott & Russell Counties, roughly following an abandoned CPR corridor until about Hawkesbury, at which point it would cross into Quebec (following an older abandoned CNoR route) to Laval, then continue south into central Montréal, though not necessarily the existing Central Station (this would likely require a new tunnel under Mount Royal). The Montréal station appears to be a terminal for trains coming from Ottawa and from Trois-Rivières and Québec, much like the existing VIA Central Station.

Alto’s next phase towards Toronto could follow one of two broad routes between Ottawa and Peterborough, either just north of Highway 7, through the Canadian Shield, or a southerly alignment through the Rideau Lakes region and then through South Frontenac and passing near Stirling and Campbellford. All planned routes would require passing through Ottawa entirely on the Ontario side of the Ottawa River, making a through station particularly likely, especially for the critical Toronto-Montréal market.

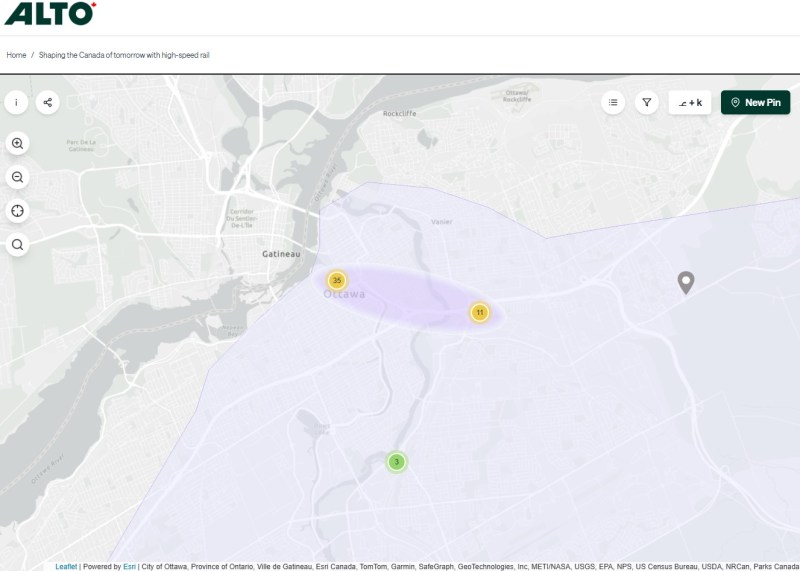

On the detailed consultation map, highlighted areas show where the seven station locations are being considered.

The idea of a downtown Ottawa Station for the new high speed rail corridor is certainly enticing. It would breathe new life into a 114-year-old landmark, provide a very convenient spot for Ottawa politicians, public servants, business travelers, tourists, and students attending nearby University of Ottawa. Rideau O-Train Station is less than two blocks away. However, it would require a new tunnel and/or elevated structure to reach the station from the rail corridors to the south. Furthermore, Centre Block would have to reopen on schedule so the Senate can move back before construction can start on refurbishing the station for passenger service.

The 1966 Ottawa VIA Station, on the other hand, has its own advantages. There is plenty of room to build new high speed train platforms, which should provide level boarding for efficient passenger movement. There is also room for parking, passenger pick-up and drop-off, as well as easy access to the highway, unlike Union Station. With the closure of the Ottawa bus station, the VIA Rail Station has become a multimodal hub, with Ontario Northland, Flixbus, and Orleans Express all using the station’s driveway, along with a KLM/Air France shuttle to Dorval Airport. There is also a dedicated O-Train LRT station on-site, though it could be better integrated with the station building.

Perhaps most importantly, the existing VIA station can help ensure the existing Corridor service remains integral, as passengers from Kingston, Belleville, and elsewhere on Lake Ontario and the St. Lawrence River will not be served by Alto; neither would Casselman, Alexandria and Dorval. That the station is a through-line, and not a stub-end terminal, will also ensure that the crucial Toronto-Montréal market will see minimal delays from back-tracking and reversing at a downtown terminal. Though there are instances of high-speed trains reversing directions at major hubs — Trenitalia’s Frecciarossa mainline between Milan and Salerno turns back at Roma Termini and at Napoli Centrale — this is an uncommon arrangement.

All the planned Alto high speed rail stations will have to be easily accessible and close to the downtown cores of the cities it serves. At this point in the planning process, this looks like it will be the case at all three big city stations. But it will need more than walk-up traffic like downtown office workers and tourists; it will be most successful as part of a complete network of local, regional and intercity transport, including the conventional VIA rail system. With specific improvements, including new platforms and better O-Train station integration, the modern yet historic 1966 Ottawa Station is well suited for all of these needs.

2 replies on “Ottawa’s Union Station problem”

Seems to me a direct Montreal-Toronto high speed rail should not detours by Ottawa.

So, just to be clear, Toronto, Montreal, and Quebec will all (very likely) get downtown stations they will all benefit immensely from, but Ottawa with the 3rd largest metro population across 2 provinces, nation’s capital, terminal station (until the entire line’s completion), and one of the two majour stops of the first phase, can’t have that because it would require new infrastructure on a $90 billion project, and it would add a few minutes to Toronto <-> Montreal? Oh, sorry, can’t forget that Ottawa Via Rail has regional buses, and highway access that is antithetical to a project trying to reduce car dependence and completely unsustainable long-term.

As for Toronto <-> Montreal, while they do have the largest number of flights, across all modes of travel, it’s actually Ottawa <-> Toronto that sees the most traffic, and Ottawa <-> Montreal that would benefit the most from a <1 hour, downtown-to-downtown link, connecting the two as one continuous economic region. Not to mention that even if you absolutely needed that express Montreal <-> Toronto travel time kept low, you wouldn’t even route through Tremblay at all – you’d go through walkley, which is exactly what ALTO has communicated.

Like, don’t get me wrong, I really quite like as a building. But it does not serve the capital region well, especially if you live in Gatineau. Union will have the Gatineau tramway on its doorstep, a direct connection to Rideau (a more central station on the entire network, and yes, you can take that as a given), and a variety of OC+STO buses, while being situated downtown, and in the cultural heart of Ottawa.